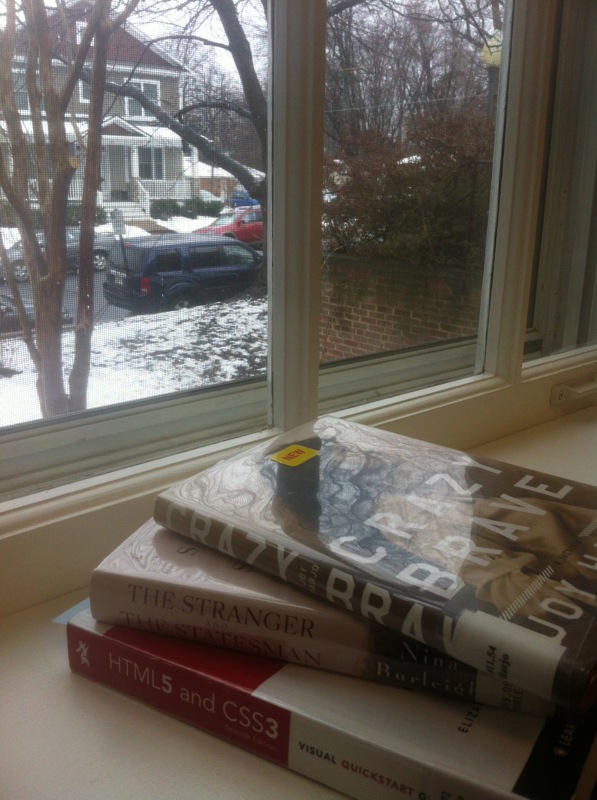

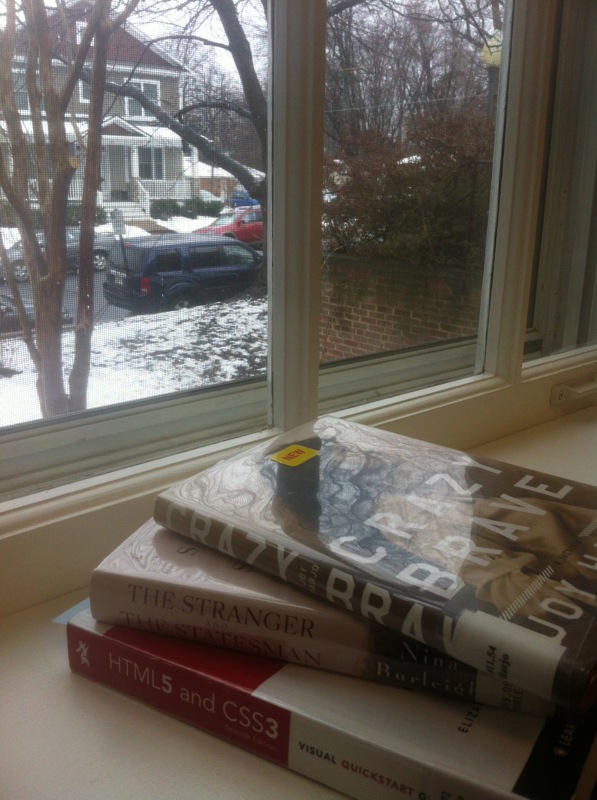

In a nearby library, there’s a new releases section that’s quite large and totally dominated by male writers. There were exactly five by women among the forty or fifty highlighted books. Two were cookbooks disguised as diet advice, and one turned out to be by a man with the unusual first name of Mallory. Another was a self-help guide. The fifth was Crazy Brave. Amidst all those colorful book jackets, the sepia-toned cover photo of Joy Harjo in profile wearing a simple white shirt and long, beaded earrings stood out.

In a nearby library, there’s a new releases section that’s quite large and totally dominated by male writers. There were exactly five by women among the forty or fifty highlighted books. Two were cookbooks disguised as diet advice, and one turned out to be by a man with the unusual first name of Mallory. Another was a self-help guide. The fifth was Crazy Brave. Amidst all those colorful book jackets, the sepia-toned cover photo of Joy Harjo in profile wearing a simple white shirt and long, beaded earrings stood out.

Considering that it was the day after Palm Sunday and the reading of Christ’s passion, perhaps I should not be surprised by the connection I felt to this award-winning writer and musician who journeyed through oppression to triumph. There are certain stories that are lived over and over for a reason.

Harjo remembers herself as sensitive child given to playing with bees who let her treat them as dolls and dreaming of alligators who seized her to live in their world shortly after she survived a polio scare, yet she survived the pain of her parents’ divorce, her father’s disappearance and her mother’s baleful second husband. He had been charming during courtship, but within days of marriage, Joy, her mother, and three younger siblings were not merely tiptoeing through a desert of potential violence but balancing on a fishing line strung between their hopes and his cruelty. Her mother had to choose between enduring the abuse or being murdered for trying to leave; they all knew he would carry out his threat to kill them should they escape. At that time, the police were more likely to reinforce an abuser’s sense of superiority than rescue his victims.

As Harjo entered her adolescence, this cauldron of fear and power became a recipe for self-destruction and rebellion. Her step-father threatened to send her to a fundamentalist Christian boarding school, but by then she had seen more than enough hypocrisy – the people who wouldn’t sit near her family in church because they were Indian and her parents were divorced, the supposedly biblical superiority of white people over all others and men over women, the white minister who forced Mexican American guests to leave his church because their brownness distracted him from his sermon, the ban on visions and prophecy, and the prohibitions against dancing. None of that sat right with her, though she loved reading the Bible and did so frequently.

Her heritage provided her doorways to both Native American spirituality and the Christian faith. Born to a Creek/Canadian father and a Cherokee/Irish mother, she lived in Tulsa, Oklahoma, surrounded by the tribal traditions of her family, the storytelling and dancing that defied assimilation. Her great-grandfather, Henry Marcy Harjo, was a Canadian missionary to the Seminole people of Florida, where he later owned a plantation bought with oil money from his wife Naomi’s family lands in Oklahoma. Another great-grandfather, Samuel Checotah, was a chief who was physically beaten in punishment for his conversion to Christianity. As a teenager, Joy recognized the prophetic love of Jesus Christ through his words and deeds but she found his followers coming up extremely short.

The cultural revolution of the sixties was therefore quite appealing to her. “Love, love, love… was the opposite of living in a house with a man who stalked about looking for reasons to beat us.” She considered running away to San Francisco but an inner voice warned her that embracing the hippie lifestyle of drinking, drugs and supposedly free sex would lead to an early death. Fortunately for all of us, she sought out an Indian boarding school and was accepted at the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe. It was her sketches that saved her. Harjo had recognized at an early age that she approached art projects differently from other children; not only did she venture outside the lines, she chose her own color schemes. Art classes became one of her few refuges.

And here is where the story of a Native American girl growing up in the sixties intersects with Holy Week in 2013. In pushing the boundaries of social expectations and cultural traditions, in recognizing her status and the value of her people, and in persevering through countless obstacles, Harjo traverses her own Via Dolorosa and, like Christ, emerges triumphant.

Her perseverance is astounding; the poverty of her first marriage and treachery of that mother-in-law would have flattened a weaker person. She could have used her beauty and talent to pursue fame on the stage or in film, but instead followed her heart to raise two children while pursuing a university degree. She might have ended up dead, killed by her abusive second husband. Instead, she turned her own home into a refuge for tribal women facing the triple shame of abuse, divorce and community betrayal. She could have rejected her heritage and used her education to escape, but instead she amplified the voices and traditions of her people. Today she is an elder, one who remembers the past and leads towards a better future. For me, her story is a great inspiration, a gift of love and an example of hope.